By Sara Scarlet, MD, written along with her mother, Susan Scarlet, BSN

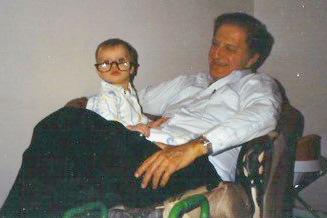

Sara Scarlet as a toddler with her grandfather in the late 1980s: “I have fond memories of visiting him at his surgical practice throughout my childhood. His penchant for surgical science and the strong relationships he forged with his patients shaped my early views of medicine and ignited my passion for surgery.”

In loving memory of my grandfather, my first physician mentor.

Earlier this year, my 90-year-old grandfather passed away unexpectedly after undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). Similar to many elderly patients who die each year in the United States, his death was preceded by a litany of costly and time-consuming tests and treatments. Despite this extensive workup, the end of his life was shadowed by suffering left unaddressed. But, unlike the thousands of elderly patients in similar circumstances, my grandfather was an experienced clinician, having practiced medicine for over 50 years.

My grandfather graduated from medical school in 1953. Before that, he had served in World War II, flying a B-29 Superfortress. With his uncanny ability to maintain composure in the most challenging of circumstances, he was emblematic of the classic surgeon archetype. A tireless clinician, he performed over 6,000 operations during his career. He came face to face with death in operating rooms, emergency rooms, and intensive care units. I do not know how he approached end of life conversations with his patients and their families. However, I do know that despite facing a life-threatening diagnosis in his nineties, he remained a “full code” until the day he died.

A few months prior to his death, he developed shortness of breath and shoulder pain. Tasks that had been easy just months just before became impossible. He began navigating the medical system with the help of his daughter, my mother, albeit several states away. He scheduled an appointment with his internist. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a likely culprit – aortic stenosis. He was referred to a cardiologist who continued the diagnostic workup. A TAVR was recommended. My mother inquired – how had his physicians discussed options for symptom control? Had they addressed the possibility of opting for comfort-focused care instead of the procedure? They had not. Despite many face to face encounters during this workup, discussions with my grandfather regarding his goals of care were limited. Rather than taking this more holistic approach, he was diagnosed with a single problem, aortic stenosis, and presented a single solution, TAVR.

But my grandfather did not have a single problem.

My grandfather became cachectic. A nagging pain in his left shoulder worsened, for which he saw multiple clinicians. With his eldest daughter and grandson at his side, he underwent the TAVR at a world renowned institution. His shoulder pain, although present prior to the procedure, was attributed to arm positioning during the case. Later, he saw an orthopedist who recommended an MRI. The orthopedist who ordered the MRI had his nurse call my grandfather to report the results, which came as a surprise to everyone. The findings were suggestive of invasive lymphoma. My grandfather phoned his internist, who prescribed analgesics for his worsening pain. An electronic referral had been placed with oncology for further diagnosis and workup.

In hindsight, the cause of his shoulder pain, dyspnea, and cachexia was clear. Disheartened, I wondered if his internist had attributed the shoulder pain to angina or osteoarthritis, or had simply downplayed the pain as status quo for a 90-year-old. I thought of the two CT angiograms of his chest he had several weeks prior to his TAVR, and all of the providers who had reviewed the studies. I imagined their eyes quickly scrolling through the images, evaluating the dimensions of his stenotic aortic valve. Did they see the significant axillary lymphadenopathy, or had the indication for the study – “evaluate for TAVR” – led to tunnel vision?

His weakness and pain became so severe that he was unable to bathe for ten days. Demoralized, he presented to a local emergency room alone. He later told my mother that he was astounded when the provider examining him did not remove his shirt or fully examine his shoulder. The emergency room team learned nothing of his lost ability to feed or bathe himself. Instead, they sent him home and encouraged a follow-up with his orthopedist. Had they really seen the whole picture?

At home, he was miserable. For years, my grandfather had been staunchly independent, living alone and turning down offers of support. For the first time, he seemed to truly acknowledge his frailty, and he was wholly unprepared. My mother began the complicated process of organizing his things in preparation for a transcontinental move. His turmoil was apparent as he grappled with the loss of his independence.

A few days later, my grandfather died unexpectedly, alone in his home. Reflecting on the end of his life, I couldn’t help but think, the countless health care professionals who had looked after him had failed to see the whole picture – he was a frail 90-year-old dying of lymphoma. Rather than address the elderly man on the exam table, they honed in on his chief complaint – aortic stenosis. The healthcare system that he was once a part of, in which he so passionately believed in, had seemingly failed him.

Health care in the United States has become more compartmentalized than ever before. The vast majority of physicians – approximately two-thirds – are subspecialists, according to a 2015 AAMC report. My grandfather’s experience prompts me to consider my own place in the medical system. Clinicians often practice in silos, and all too often, we get tunnel vision. We see a 90-year-old man and quickly zone in on the chief complaint or reason for consultation listed in the medical record, rather than making an effort to recognize the whole person. Why?

As I coped with the loss of my grandfather, his story played over and over again in my mind. I considered the providers who had seen him in his last weeks of life and wondered if I was guilty of the same behaviors. Reflecting on my own experience, I recognized that the great volume of patients and the increasing burden of administrative tasks have a tendency to shift our focus away from the bedside. I considered my role as chief surgical resident on call, quickly scurrying from stretcher to stretcher in the emergency room. I thought of the countless patients I had seen with circumstances similar to my grandfather’s. I remembered evaluating a 93-year-old woman with a large bowel obstruction. Just as I began to address her goals of care, the harsh chime of my pager cut through the air – “red trauma, ETA 5 minutes.” I worried that I would be forced to focus solely on her chief complaint in the limited time that remained. Doing so would afford me little time to have a more meaningful discussion. Would I too miss the opportunity to dig deeper? How many of my future patients would suffer due to similar constraints?

After my grandfather’s death, a colleague pointed out the “whole person care” movement. Often acknowledged in the context of palliative care, “whole person care” recognizes the dichotomy that exists between curing and healing, focusing primarily on the relief of suffering. Whole person care is slowly gaining momentum across the United States, with “whole person” clinics cropping up in places like California and North Carolina. Before becoming a physician, I would have been surprised to find that not all clinicians practice “whole person care.” With its promise of healing and curing, shouldn’t we all be “whole person”-oriented?

We must not think of ourselves as system-specific clinicians. Gastroenterologists, cardiologists, allergists, and general surgeons – we all treat the whole patient. We must avoid tunnel vision at all costs.

I like to imagine an alternate scenario for the end of my grandfather’s life. One in which he sat down with an internist, who patiently listened as he voiced concerns about the worsening pain in his shoulder and who took note of his frailty. One in which the radiologist called his cardiologist to ensure she had also seen the diffuse lymphadenopathy and considered it as she developed her differential diagnosis. One in which the TAVR was postponed prior to oncology consultation. One in which the oncologist had meaningful discussions regarding goals of care and palliation. One in which he declined chemotherapy and radiation, which was not consistent with his life goals, in favor of comfort. A future in which he would have died at home with hospice care, surrounded by the family members who loved him.

Sara Scarlet, MD is the fifth-year general surgery resident at the Department of General Surgery at UNC Chapel Hill and a member of the Gold Humanism Honor Society. She is currently pursuing advanced training in public health and bioethics. She aspires to a career in trauma surgery. In her future practice, she hopes to study the intersections of trauma surgery, public health, and surgical ethics. Follow her on Twitter at @SaraScarletMD.

Sara Scarlet, MD is the fifth-year general surgery resident at the Department of General Surgery at UNC Chapel Hill and a member of the Gold Humanism Honor Society. She is currently pursuing advanced training in public health and bioethics. She aspires to a career in trauma surgery. In her future practice, she hopes to study the intersections of trauma surgery, public health, and surgical ethics. Follow her on Twitter at @SaraScarletMD.

Susan Scarlet, BSN practices at the North Florida-South Georgia Veterans Health System in Gainesville, Florida. She has practiced nursing for 40 years and has cared for people from diverse walks of life, from infants in the neonatal ICU to veterans in a palliative care unit.